To enact EU policies and foster solidarity between Member-States, the EU collectively decides on EU laws. These laws are written and voted upon through the EU’s main institutions: the European Commission, the European Parliament, and the Council of the EU. Each performs similar roles to the democratic institutions we might be familiar with in our countries.

The European Commission is the executive branch of government. The legislative branch is conjointly formed by the European Parliament and the Council of the EU. At this stage, all we need to consider is:

- The European Commission represents the collective interests of the EU as whole. It is composed of 27 European Commissioners.

- The Parliament represents the interests of EU citizens. It is composed of 705 elected Members of the European Parliament.

- The Council of the EU represents the interests of the 27 EU governments. It is composed of 27 Ministers.

Following this logic, we can formulate the first explanation on how decisions are made:

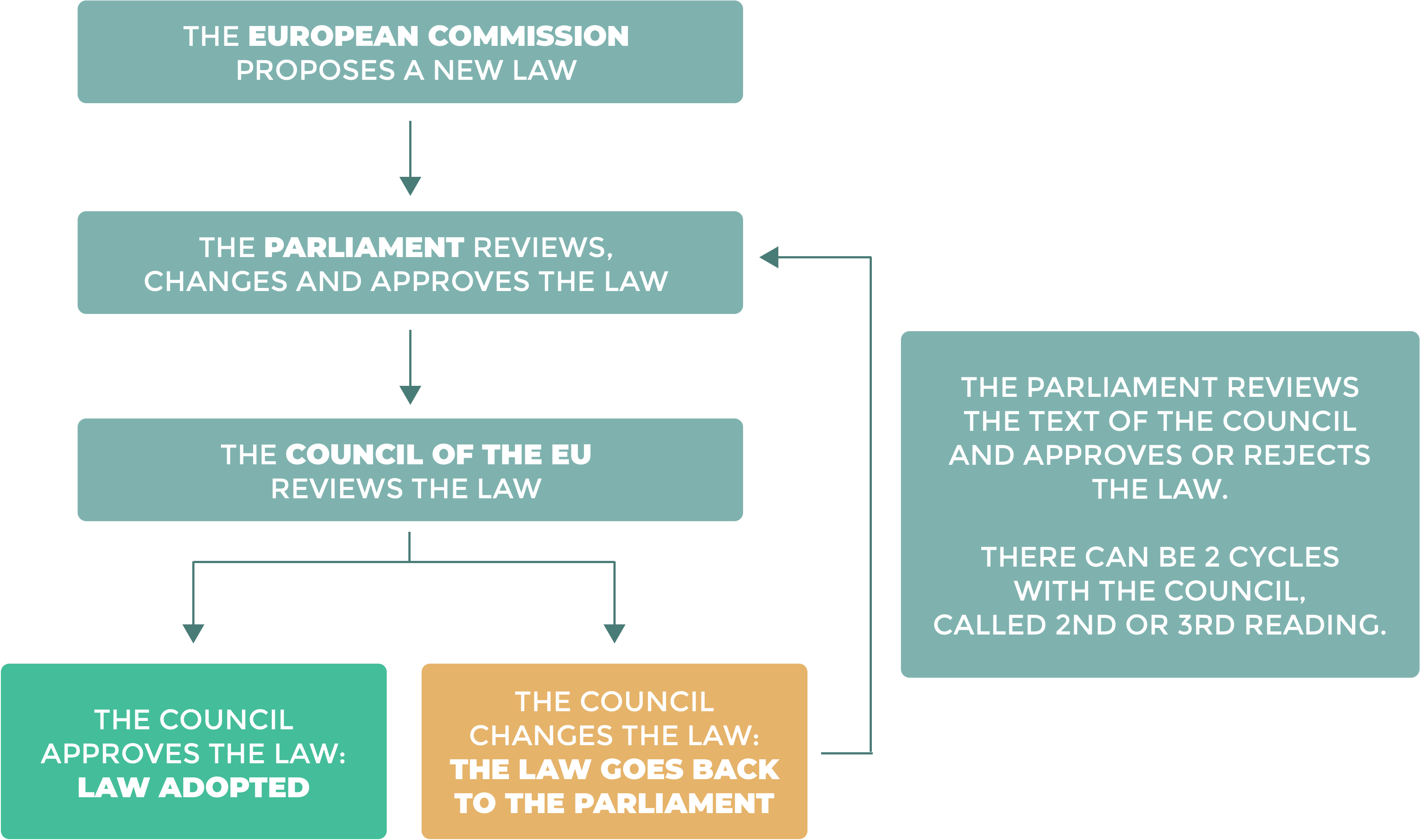

The European Commission proposes new laws. The European Parliament and Council of the EU suggest changes and must conjointly agree to adopt the final text of the law. If they fail to agree, the law is rejected. The Parliament and Council have 3 chances to agree before the text is rejected.

In practice, laws adopted by the EU institutions come in two varieties: regulations and directives. Regulations are EU laws that apply uniformly across EU countries. Once they have been approved, they automatically apply across the Union. Directives are EU laws that set common objectives but leave it up to EU countries to decide how to reach those objectives.

These laws are enforced by the European Court of Justice and national courts. The EU is a single legal order. There is no distinction between the national and EU-level in the most integrated areas of cooperation.

Given the difficulties involved in achieving agreement among 27 countries, 3 EU institutions and, increasingly, 430 million EU citizens, the name of the game is compromise. The EU simply cannot function without it. Every 6 months, the Heads of States and Governments of the 27 EU countries gather in Brussels to form the European Council. (NOTE: the European Council and the Council of the EU are two separate entities.) Despite the media attention given to these events, the European Council is not involved in legislation. It exists solely as a forum of compromise designed to resolve deadlocks and provide general direction to the overall political aims of the EU.

The stage is set. Let’s imagine that the EU wants to adopt a new law.

How does this work in practice?

Step 1

The European Commission proposes a new law. The draft text is written taking into account the opinion of EU governments, Members of the European Parliament, external experts, lobby organisations and your opinion.

Step 2

The European Parliament and the Council of the EU examine the draft text and suggest changes.

Members of the European Parliament and representatives of EU countries will work separately on amendments, based on their political preferences and external expertise from lobby organisations and citizens. The European Commission follows the discussions closely and seeks to defend its original vision.

Members of Parliament will internally work on a report through lead committees. Representatives of EU countries will form working parties based on the policy area the draft text is targeting.

Step 3

Once both the Council and the Parliament have followed their internal procedures to approve the amended text of a law, they will organise a meeting with the European Commission to compare the texts and conjointly work on a final version. These meetings are called trilogues and form the main method through which laws are adopted.

Step 4

If a final text is agreed upon, both institution will take a final vote. MEPs will gather in a plenary session to approve the text, while Ministers of the EU countries will gather in the Council to do the same. If both approve the final text, it becomes EU law.

Step 5

The Council and the Parliament have three chances to approve a draft text before it is rejected. However, in reality the majority of texts are approved after the first round of amendments and negotiations. The Commission can at any time decide to remove a draft text if it believes that other institution are no longer in line with the original vision.

The graph below details EU law-making in a nutshell: